Ever wondered what names echoed through the bustling streets and quiet villages of England during the 18th century? It was a time of immense change, from scientific discoveries to burgeoning empires, yet some aspects of life, like family names, retained a steadfast tradition. Delving into the past to uncover the common English last names 1700s offers a fascinating glimpse into the lives of ordinary people, their occupations, their locations, and their familial ties long before modern record-keeping made such insights readily available.

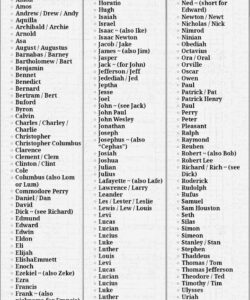

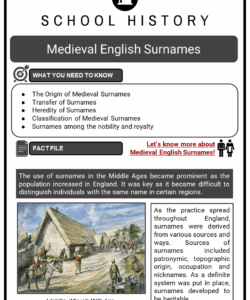

Surnames, as we know them today, had largely solidified by the 1700s, but their origins stretch back centuries, rooted in practical descriptions. These early identifiers typically fell into a few main categories: patronymic (derived from a father’s name, like Johnson for “son of John”), occupational (based on a person’s trade, such as Baker or Cooper), locational (indicating where someone lived, like Hill or Sutton), or descriptive (referring to a physical trait or characteristic, like Brown or White). By the 18th century, these names were firmly established across generations.

Understanding these historical surnames isn’t just a genealogical pursuit; it’s a way to connect with the social fabric of an era. It helps us paint a clearer picture of communities, trades, and migration patterns that shaped England. Imagining a bustling market square or a quiet farming community, the people who carried these names were the everyday fabric of society, their identities etched into their very names, passed down through time.

The names that dominated the English landscape in the 1700s weren’t complicated or exotic; they were reflections of daily life. They speak volumes about a society where one’s livelihood or place of residence often defined their public identity. This practicality meant that names associated with highly common professions or physical attributes would naturally appear with greater frequency across the population, making them truly ubiquitous.

While the spelling might have seen minor variations across different regions or due to literacy levels, the core forms of these surnames were incredibly stable. This stability is precisely what allows us today to look back and identify patterns in English nomenclature. These names carried the weight of generations, linking individuals not just to their immediate family, but to a much wider lineage that had deep roots in the British Isles.

A Glimpse into Common English Surnames of the 18th Century

- Smith: An occupational name for a blacksmith, an absolutely essential trade in any community.

- Jones: A patronymic name, meaning “son of John,” a very popular given name in medieval England.

- Williams: Another incredibly common patronymic surname, signifying “son of William.”

- Brown: A descriptive name, often referring to someone with brown hair, eyes, or complexion.

- Davis: Yet another patronymic, derived from the given name David, meaning “son of David.”

- Miller: An occupational name for someone who operated a mill, grinding grain into flour.

- Wilson: A patronymic surname, meaning “son of William,” similar to Williams but with a different suffix.

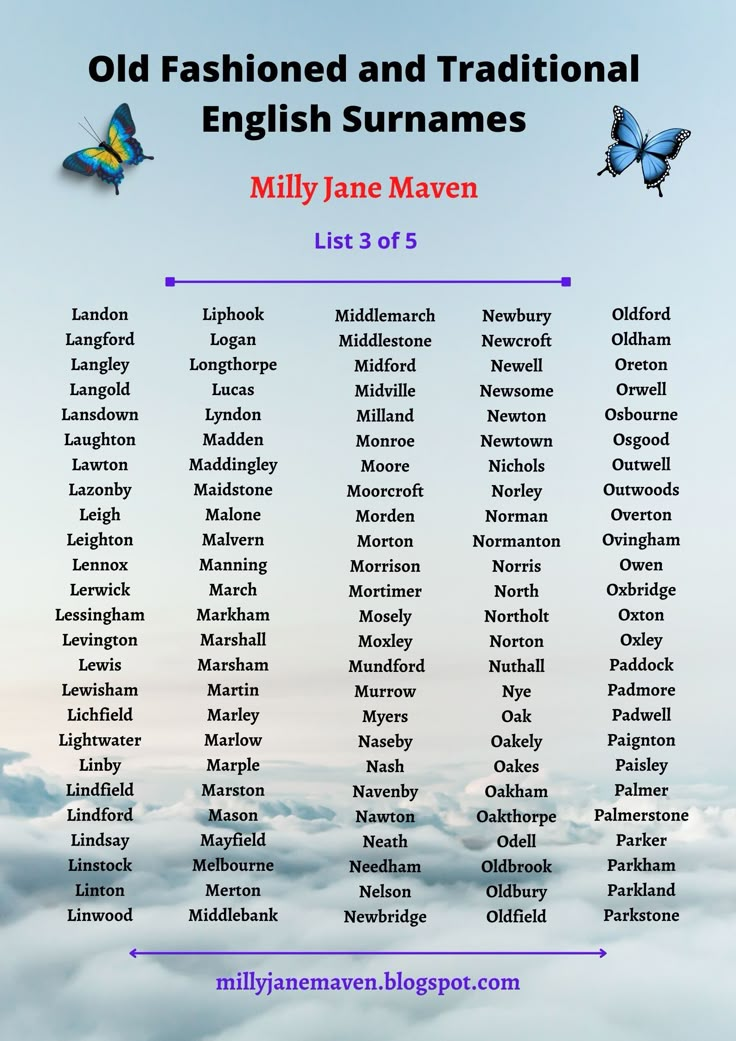

- Moore: A locational name, indicating someone who lived near a moor, heath, or marshland.

- Taylor: An occupational name for a tailor, a crucial profession for clothing families.

- Johnson: A very widespread patronymic name, meaning “son of John.”

- White: A descriptive surname, referring to someone with fair hair or a pale complexion.

- Martin: Derived from the personal name Martin, a popular saint’s name.

- Anderson: A patronymic surname, meaning “son of Andrew.”

- Thompson: Meaning “son of Thomas,” another very common given name.

- Walker: An occupational name for a “fuller,” someone who treated cloth, or a forest official.

- Robinson: A patronymic name, meaning “son of Robin,” a diminutive of Robert.

- Green: A descriptive or locational name, referring to someone living by a village green or a green spot.

- Hall: A locational name for someone who lived or worked at a large house or manor hall.

- Lewis: Derived from the given name Lewis, of Germanic origin, often linked to nobility.

- Wright: An occupational name for a craftsman or builder, such as a wheelwright or shipwright.

These names weren’t just common; they were the backbone of English identity for centuries, and many continue to be among the most frequently encountered surnames across the English-speaking world even today. The dominance of occupational and patronymic names particularly highlights the societal structure of the time, where a person’s role in the community or their immediate lineage was a primary identifier.

The 1700s saw a growing need for more systematic record-keeping, from parish registers documenting births, marriages, and deaths, to land deeds and census-like surveys. This increasing bureaucracy further solidified the use and spelling of these common English last names 1700s. As families moved, whether within England or emigrating to new colonies, they carried these established names with them, spreading their prevalence even wider.

It’s fascinating to consider how these simple monikers, born out of necessity and straightforward description, have endured through generations, connecting us directly to the past. Each name, in its own way, tells a mini-story about a time when life revolved around local trades, family connections, and the landscape itself. They are linguistic fossils, preserving echoes of an earlier world.

Reflecting on these prevalent surnames offers a quiet contemplation on the passage of time and the enduring nature of human connection. They serve as a powerful reminder that while technology and society evolve dramatically, the fundamental human need for identity and belonging remains constant, often encapsulated in the very names we bear.

Ultimately, these names are more than just labels; they are threads in the vast tapestry of English history, each one a link to a countless line of ancestors who lived, worked, and loved in the 18th century. They resonate with the past, informing our understanding of heritage and reminding us that history is not just about grand events, but also about the individual lives that collectively shaped an era.